On friction

Dear designer,

This is my first post of what I hope (fingers crossed) to be more. May the stories and reflections I share here help you along your journey in(to) the world of games UX.

For as long as I have known about UX, friction has been somewhat of a taboo.

Good design is actually a lot harder to notice than poor design, in part because good designs fit our needs so well that the design is invisible - Don Norman

I don’t know how you felt the first time you read that quote. For me, although it was Don Norman’s words, I heard it in Morgan Freeman’s voice. Taken at face value, UX is about creating clarity and simplicity. Our job is around understanding and anticipating user needs; fulfilling them before they think to ask. Even our language to describe great design seem like extensions from that quote: ‘natural’, ‘intuitive’, ‘smooth’.

If those words are synonyms for design virtues, then ‘friction’ implicitly was some sort of design sin. Friction is loud. Whether it’s grass burns from little league or watching your team's Yasuo hit their 0/10 power spike - friction is something you notice. It demands your attention - a far, far cry from invisible. Frictious design was bad design. This is what I internalized early on and would only receive my first real lesson otherwise a couple years into my career.

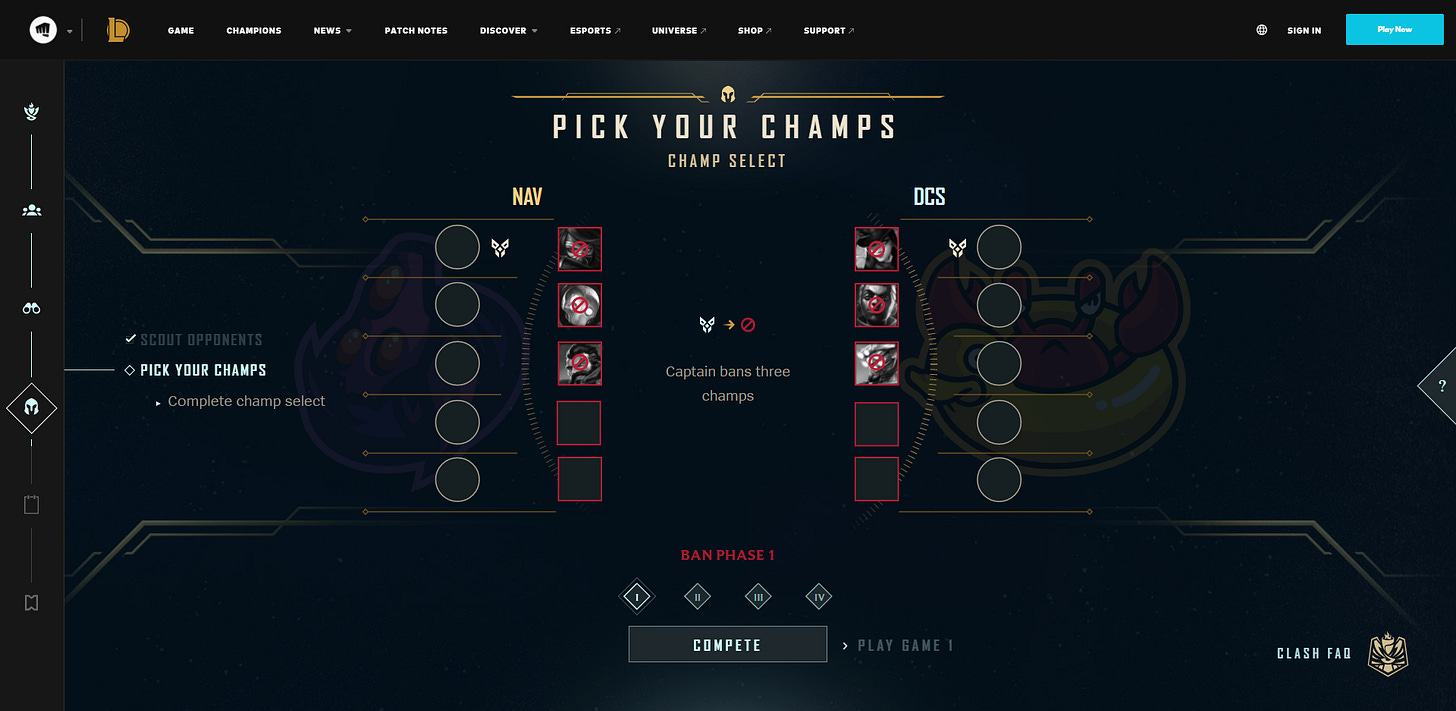

It was 2018, I had recently transitioned from the Web Design team at Riot to the Competitive Systems team on League of Legends. At the time, we were working on the release of our much anticipated tournament system - Clash. During one of the conversations in the pit, the team was brainstorming different ways we could expand Clash's engagement with the player base and make the experience more accessible.

As the UX designer on the team, my training and tendencies led me to examine the player journey, identify the biggest sources of friction, and then advocated for eliminating them. Along that line of thinking, this was my reasoning:

A huge part of our player base mainly spend their time specializing in playing one champion, especially in competitive contexts

The presence of bans means players have to invest outsize time practicing alternatives because their favorite champion may be unavailable.

Coordinating a team of 5 people to get together and commit an afternoon was already hard enough. Why add any more friction to a high stakes situation that set players up for potential failure?

Therefore, we should remove bans from Clash:

On paper and in a vacuum, this line of thinking sounds reasonable. But as my producer (Leanne) and game designer (Jon) counterparts would tell me, and as I will now tell you, this is a naïve and narrow way to look at it. No friction, no problems is a reductive way of breaking down experiences, especially for games. This is one of the biggest things I had to unlearn and relearn.

Leanne and Jon reminded me that bans are a huge part in what makes Clash special. Scouting what your opponents play, adjusting your draft, pre-tournament preparation - all of these decision spaces are less rich in a world without bans. On top of that, the thematic fantasy of Clash is competing like the pros do, with bans representing an important part of that thematic fantasy.

Bans are a source of critical friction for Clash. They add value to the experience despite their frictional nature. Removing bans in this case would be akin to taking players who wanted to try diving in the deep end and putting them in the kiddie pool. Everyone might have an easier time keeping their head above water, but nobody really gets to swim.

Since then, I've continued to think more about friction as a designer. Compared to traditional web products or productivity applications, games are uniquely charged with friction. Games are only fun when choices feel like they have meaningful outcomes. In order for outcomes to have meaningful consequences, they must be imbued with some amount of friction. Winning only means something if losing was a real possibility. A Pentakill only carries weight because of how challenging and rare it is to pull off. What we gain too easily we esteem too lightly, and that’s all the more true in games.

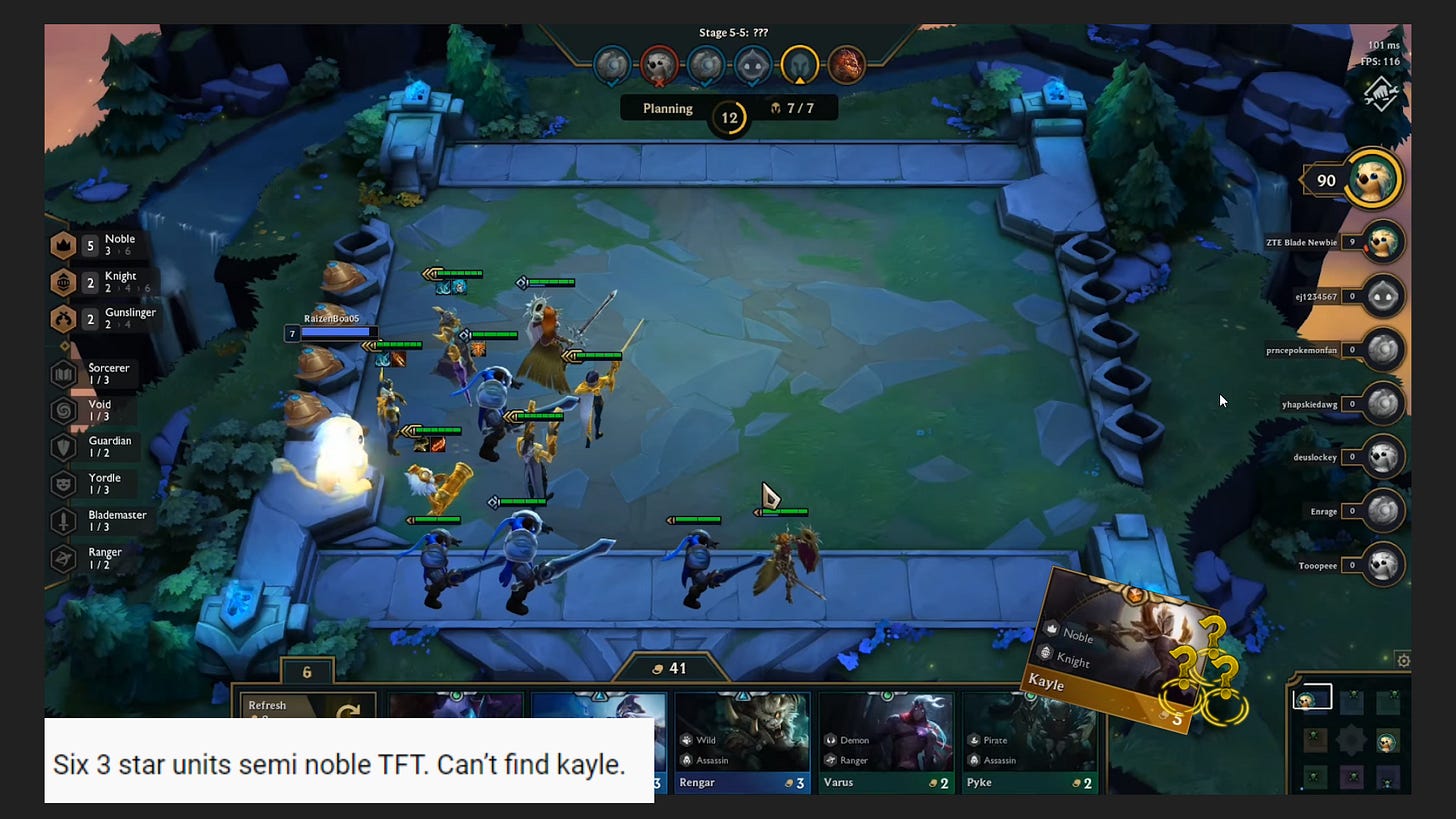

Don’t get me wrong, this isn't to say friction is always good. Thing can always be harder but that doesn't mean they should. I could force players to solve a Calculus problem each time they tried to buy an item in League of Legends, but that just doesn't sound fun. And while it wasn’t quite Calculus, we did create a different math sized problem when we launched TFT. On launch, TFT had no UI to display the tier probabilities of units in the shop.

Instead of keeping the actionable information and feedback loop tight, players were forced to look up this information online or rely on third-party apps. As a result, not having this information created significantly more friction in TFT- but without servicing any positive or healthy outcomes.

In this case, not having this key piece of information created failure states that players were entirely unaware of. For example, players chasing 6 Nobles in Set 1 of TFT would spend all their gold chasing a unit they only had a 0.4% chance of finding.

We wanted players to build strategies around when they wanted to hit different units, to have rich choices around how they could plan to succeed with the team they chose. This is where the fun of the game was, so it was an easy decision to remove this particular piece of friction we launched with.

In summary, friction is something I would encourage anyone interested in game UX to explore broadly and without regard to the maxim of things like ‘invisible design’. It’s often the process of learning to doubt what we first found most obvious and sacred that we find the unexpected.

Friction may be loud but it is also intimate. Choosing to incorporate friction is picking which rough edges are especially worth keeping because they make the experience unique. Approaching games through the lens of friction empowers you to discover and define what fun is, what play means, and ultimately the shape of your game as a whole.

Refactoring my relationship with friction has been one of the most worthwhile things I’ve struggled through as a designer, and my hope is that it will be for you as well.

JZ